Is Dominance Democratic?

Hungary has been a unique country in the EU for the past decade for numerous reasons, but the most baffling of all political developments in the country is probably the fact that Fidesz has been winning election after election for 25 years with comfortable margins. Most observers from the West have explained this streak as a sign of democratic backsliding or even authoritarianism. The main question then becomes: is it normal for a party to govern for more than a decade in a democracy, or is that an unnatural phenomenon? The answer is more complicated than it appears to be.

Hungary has been a unique country in the EU for the past decade for numerous reasons, but the most baffling of all political developments in the country is probably the fact that Fidesz has been winning election after election for 25 years with comfortable margins. Most observers from the West have explained this streak as a sign of democratic backsliding or even authoritarianism. The main question then becomes: is it normal for a party to govern for more than a decade in a democracy, or is that an unnatural phenomenon? The answer is more complicated than it appears to be.

In order to find out whether this dominance is ‘normal’, we need to look at if similar situations have arisen in the past elsewhere. Most would say that all we need to do is take a look at the current European landscape to see that this kind of success is not normal since no other country has had a party this successful. This is only partially true, since Angela Merkel in Germany and Mark Rutte in the Netherlands were in power for similarly long stretches during the same time period, though they did so heading coalitions, nevertheless, being in power for a long time is not unheard of even in Western Europe.

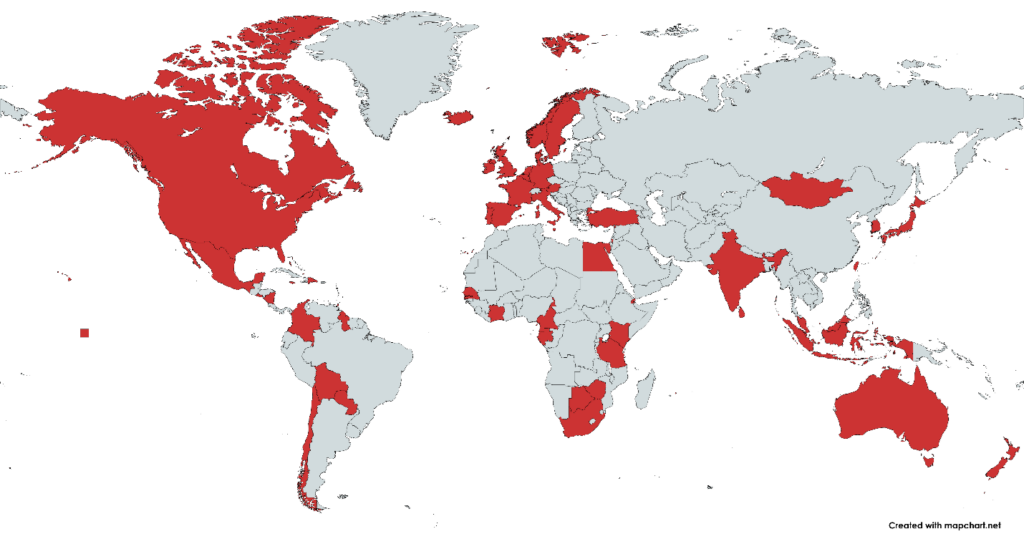

The further back in time we look, the murkier the picture becomes. Below is a map indicating the countries where, through (at least partially) democratic means, a party managed to win at least three consecutive elections during the Cold War (1946-1990). This map clearly shows that almost all of the West experienced a winning streak akin to that of Fidesz. Examples include the dominance of Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher in the UK, the success of the Christian Democrats under Konrad Adenauer and his successors in West Germany, and the victories of the Republicans under Charles de Gaulle in France. At the same time, Eastern European countries such as Hungary could not have dominant parties due to the autocratic nature of their governments at the time.

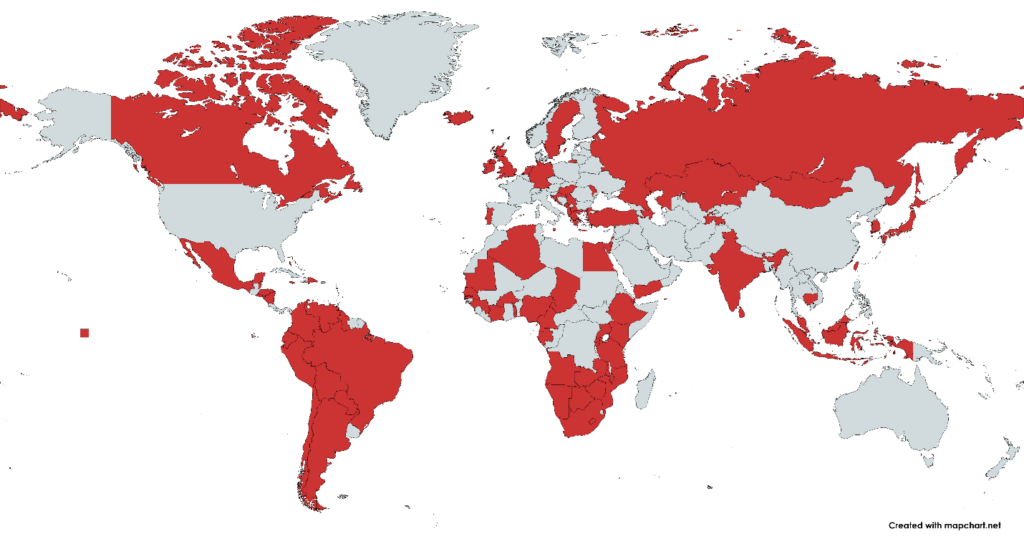

This would indicate that what Hungary is currently going through is normal, and the concern from Western commentators would even seem peculiar, since almost all of their countries have gone through the same process. The second map below explains why the West is reacting the way it does. It shows the prevalence of dominant parties after 1991. It is immediately apparent that since the conclusion of the Cold War, parties that govern for a decade or longer are mostly present in newer democracies, particularly in less developed countries, while this phenomenon all but disappeared from Western Europe.

This is a perfect explanation for why Hungary appears to be a case unlike any other: it is not similar to the current Western landscape and looks like an Eastern or even Third World country based on the continued success of one party. It should not be forgotten that the Hungarian situation also has similarities with countries such as the UK, Germany or France – but mostly resembles what they went through 50 years earlier.

This gets us to the crucial point: it appears that many countries have a dominant party system in the years after establishing democracy. Most Western European countries were freshly democratic during the Cold War and had the same governing party for decades, just like Hungary does now. As Western democracies matured, dominance has become less and less common, to the degree that nowadays, dominance seems like an unnatural fit with democracy. History shows us that this is not true: dominance is very rare if there is a well-established democratic system with a long track record, but in the first 50 years of democracy, dominant parties are the norm, not the exception. Hungary (and other younger democracies) are just ‘catching up’ with the West, and dominance could be seen as quite natural – as their democracies mature dominance will most likely disappear.

This is not to say that any concern regarding the Hungarian cabinet’s actions can be explained by these observations. The main point is that dominance is not unnatural – on the contrary, it has been prevalent in every region that introduced democratic institutions. Just because a country has one party winning election after election does not necessarily mean that it is not autocratic or violates major democratic norms – it could simply mean that it is at a stage of political development that is conducive to this phenomenon.